THL Toolbox > Tibetan Texts > Inputting a Tibetan Text > Tibetan Text Input Manual, English Version

Tibetan Text Input Manual, English Version

Contributor(s): Ben Deitle, David Germano, Nathaniel Grove, Zach Rowinski, Jed Verity, Steve Weinberger.

Introduction

This manual describes how to input Tibetan texts into computer files. If these instructions are followed carefully, the result will be computer editions of Tibetan texts that can be preserved far into the future. These computer editions are also very flexible: a single computer file can be turned into a Tibetan-style pecha, a Western-style book, a CD, or an Internet webpage. Inputting Tibetan texts into computer file consist of three sets of broad activities:

- Input and proofing

- Critical editions

- Markup and formatting

The present manual covers #1 and #2, whereas a separate THL manual covers #3.

Over the last two decades, personal computer technology has grown and there has been widespread Tibetan text input. However, this work has been done in a haphazard fashion and has not used the best standards or technologies. The problem is that many of the texts that have been entered are not suitable for archiving, as the technology used to create them will soon be outdated and unusable. The result of all this is that despite the work that has been put into them, many of today’s electronic editions are less reliable, less useful, and less durable than the paper copies from which they were created.

The goal of this manual is to resolve these problems. The process of creating durable and usable electronic texts is not difficult, and simply involves following a few essential principles from the beginning of a project:

- Use only a well made Unicode font for input, such as Tibetan Machine Uni.

- Save the text in a format that will be durable and can be converted into a variety of different print and electronic formats.

- Input the text exactly as it is, errors and all, to preserve an exact copy of a known print edition. If you want to correct errors in the text then you must follow our guidelines so the original reading of the manuscript is preserved along with the correction.

- Be careful and consistent in inputting every element of the original text and in not adding any additional elements such as extra spaces, etc.

- Insert pagination and lineation of the original print copy.

- Input must be done carefully and proofread carefully – an input text with many mistakes is of no use to anyone

- Carefully proofread by checking a printout of the input text against the original; do not just proofread from the computer screen.

We hope that these instructions are useful for any project planning to input a Tibetan text. For THL text input projects, the instructions are not optional – these must be followed in every detail.

Step One: Preparing Your Computer

This section describes how to prepare your computer with the necessary font, keyboard, and word processor to input Tibetan Unicode.

1. Font

Obtain a Unicode Tibetan font. For THL work we require use of the Tibetan Machine Uni font, which is obtainable for free from the Tibetan Machine Uni page.

Please note that as of November 3, 2005 this font is in release 1.0, which lacks some character combinations. We are planning to have release 2.0 available before the end of 2005. If release 2.0 can’t produce a necessary character, please contact us at <a class="safe-contact" href="javascript:linkTo_UnCryptMailto('nbjmup;uimAdpmmbc/jud/wjshjojb/fev');"><img src="/global/images/contact/contact-thl.gif" /></a> and we will investigate and respond.

2. Keyboard

You also need a keyboard for input of the font. The most popular keyboards are “Wylie” and “Sambhota,” though there are significant groups of users that are accustomed to other types of keyboards. See the following URL for THL’s survey of keyboards including direct downloads:

For THL Extended Wylie input, we recommend the TISE keyboard:

It is important to print out the THL Extended Wylie scheme as a reference for inputting more unusual characters:

For Sambhota input, we recommend for the moment the Keyman input method:

It is important to print out the Sambhota input scheme as a reference for inputting more unusual characters:

3. Software and Operating System Support

It is important that you are using an Operating System version and Word Processor software version that support the input and display of Tibetan Unicode fonts. At present operating systems prior to Windows XP do not support Tibetan Unicode fonts. The optimal configuration is to run Windows XP in its most up-to-date version and Microsoft Word (2003 SP1) in its most up-to-date version. However, if you have Windows XP but use Word 2000, see the following THL documentation on configuring Word to handle Tibetan Unicode:

See also "Appendix D: Inputting Using a Non-Windows Operating System and Software"

Step Two: Creating a New Document

This section describes how to create the word processing document into which you will enter the text. These instructions are currently based upon using Microsoft Word. There are three steps in this process.

1. Obtain THL Word Templates for Creating New Word Documents

First you should obtain the THL templates that must be used for creating Tibetan language documents in Microsoft Word. This template is called TibetanLanguageTemplate.dot, and is what is used to create a new document.

- Download the

Tibetan Language Template.

Tibetan Language Template. - Open the zip file and place the file TibetanLanguageTemplate.dot in the following folder on your hard drive:

- Windows 7: C:/Users/{Windows user name}/AppData/Roaming/Microsoft/Templates

- Windows XP: C: > Documents and Settings > {Windows User name} > Application Data > Microsoft > Templates

2. Open a New Document

First, open a new document using the TibetanLanguageTemplate.dot template. To do this in Microsoft Word:

- Go to File and then select New.

- Then when the New Document window appears, look under the Templates section and select On My Computer. This will bring up a list of Microsoft Word templates stored on your computer.

- Select the template TibetanLanguageTemplate.dot. A document will open containing a metadata table.

When inputting volumes with more than one text, such as in the Kangyur, each individual text should be saved as a separate file, no matter how short the text is.

Reasons for Using This Template: There are two reasons why it is important to use this template. First, it contains features (such as an automatic page numberer) that will make the work of entering a text much easier. Secondly, it contains a set of standard formatting styles suited for working with Tibetan texts; if these styles are used, then it will be easy to convert the text into a variety of different formats, like traditional pecha, Western books, or electronic editions.

3. Name the Document, and Save It

Once the TibetanLanguageTemplate.dot template is open, save it using a short name that is appropriate to your project. To do this:

- Go to File and select Save As

- When the Save As window appears, type in the name of your text in the File Name box

- Use the Save In box to select where on your computer you want to save it

- And click Save.

Suggestions for Creating File Names: file names cannot be very long, and they unfortunately cannot be created using Tibetan script. Thus you will need to make an abbreviated name for your text, using Roman script letters (if you know Wylie, use Wylie). Use an abbreviation based on two syllables from the text name. For instance, for the བཻ་ཌཱུརྻ་སེར་པོ་, one could use the name “baiser.” If the text is large enough to require multiple files, add the file number after the abbreviation. The first བཻ་ཌཱུརྻ་སེར་པོ་ file would be baiser1; the second file would be baiser2, etc. If the text consists of multiple volumes, enter the volume number after the two-syllable abbreviation, then enter a dash, and then enter the file number. For example, if the text you are entering had two volumes and the first volume had three files and the second volume had three files, the file names would be:

- baiser1-1

- baiser1-2

- baiser1-3

- baiser2-1

- baiser2-2

- baiser2-3

For text collections such as the Kama Shintu Gyepa or the Kangyur, we require, for example, that file names be of the format kt-d-0208-pha-01.doc, where kt is the abbreviation for the collection ("kangyur-tengyur), d is the edition siglum (Dege), 0208 is the text number in the edition, pha is the volume letter, and 01 is the number of the file for that volume (in this case, it is the first file in the volume). In filenames, be sure to use leading zeros--for example, “0” in “0208” and “01”!

For a text that spans more than one volume, there is a different filenaming format. For example, the first text in the Kangyur, which takes up the entirety of volumes 1-4, would have the following filenames:

kt-d-0001-ka-01.doc

kt-d-0001-ka-02.doc

kt-d-0001-ka-03.doc

through the end of volume ka.

Then the files for volume kha would have these filenames (remember that this is still a single text):

kt-d-0001-kha-01.doc

kt-d-0001-kha-02.doc

etc.

4. Filling out the Metadata Table at the Beginning of the Document

The new document has a metadata table at its top. This table is like an electronic version of a dpe cha label (dpe mtshan), as it helps a reader quickly identify what text is in the computer file; thus it is important that it be filled out correctly.

Tips for Filling Out the Metadata Table: The data table at the end of this document (header “Blank Metadata Table”) contains explanations of each field that needs to be filled in. Fill in every field that applies to your project. Some fields may not apply to your project; these can be left blank. For example, many Tibetan texts do not have an ISBN number or a Library call number. Likewise, a Tibetan text may not have a “spine title” or a cover page, so these fields can be left blank.

Data entry in the Metadata Table can be done in Tibetan or in English. There are two rows for every field, one row for Tibetan language and one row for English language.

To input Tibetan into a table cell, you may need to change the font for that cell. Place the cursor in the appropriate cell. Then, in the font menu, change the font to "Tibetan Machine Uni":

Then enter the data.

All dates should be given in the format, YYYY-MM-DD.

Step Three: Typing the Text

Now that you have created a document, you can begin to actually type in the text. The goal is to create an exact copy of the paper text in a Unicode font, reproducing all of the characters, punctuation, spaces, and even the errors. The ten topics below describe this process.

1. Type the Title of the Text

Above, you entered a data table at the beginning of your document. Now, on the first line after the data table, apply the Heading1,h1 style and type in the full title of the text in Unicode Tibetan. The easiest way to apply this style is to click the arrow next to the Style box located in the upper left corner of the screen. After clicking on this arrow, a list of styles will appear; scroll down and select the Heading1,h1 style. Once you have selected the style, you can type the name of the text. Titles should be given with a final shad and not a final tsheg, excepting of course no shad after a final g and a tsheg+shad after a final ng.

It is, however, much faster if you learn to use keyboard shortcuts. Shift+Alt+S will highlight the Style box above the document, and you can type in the two-letter abbreviation after the Style name (for example, the abbreviation for Heading 1 = h1) and hit enter to apply the style. This makes it much faster to select and apply styles.

While typing, make sure to use paragraph returns (not manual line breaks) and non-breaking spaces. If you click the “¶” (Show All) button in the toolbar, paragraph returns will look like this: ¶, and non-breaking spaces like this: °. On Wylie Word and Tise keyboards, for example, you can get a non-breaking space by typing in the underscore - “_” (Shift + -). Screenshot of the Show All button on the toolbar:

If the keyboard you are using does not have a keystroke for a non-breaking space, after typing in the text you can Find and Replace the breaking spaces with non-breaking spaces. To Find and Replace in MS Word, press Ctrl+H. Then, enter a space in the Find what field and enter “^s” (symbol for non-breaking space) in the Replace with field.

2. Hit Enter, and Select the Paragraph Style

After you have typed the title of the text, hit the Enter key. Then go back to the Style box and select the Paragraph,pr style. This will cause the rest of the text that you type to appear as an ordinary paragraph, in Tibetan Machine Uni font. This is the style that the rest of your typing should be in.

3. Tell Microsoft Word to “Use Line Breaking Rules”

If you find that Tibetan text is not line breaking properly – i.e. line breaks are happening in the middle of Tibetan syllables – then you must manually set the relevant option in Microsoft Word. To do this,

- Go to Tools, and then select Options.

- When the Options window appears, select the Compatibility tab.

- Then, in the list of Options, scroll down until you see the option Use Line Breaking Rules.

- Click the box next to this so that a check appears inside the box.

- Then click OK.

You will need to do this for every new file that you create. The Options window under Tools will look like this:

4. Enter the First Page Number

The document you have created contains an automatic page-numbering function. Before typing a page, you can use the page-numberer to set and then insert the page number. Once the page number has been inserted, you can proceed to type the text on that page. When you are done typing the text on that page, you insert the page number for the next page, and then type the text from that page.

Note that the page numberer inserts page numbers in the text itself. For example, if the last word on page 230 is ཞེས་ and the first words on the page 231 are པ་དང༌།, then the resulting typing will look like: ཞེས་[231]པ་དང༌།. Although the page numbers appear in the text, when the computer file is used to print a pecha or a book, these numbers can be automatically removed and placed on the side of the page (in the case of pechas), at the bottom of the page (in the case of books), and so on.

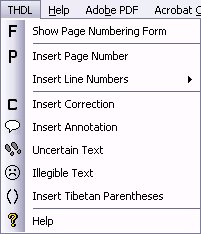

Now, set the first page number in your project. There are two ways to do this:

- Click on the "P" button on the THL toolbar, or

- Press Ctrl+1 (in other words, hold down the “Ctrl” key and press the number “1” key).

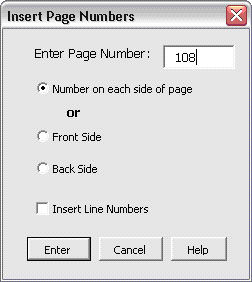

Both methods will cause a window to appear that says: "No page number has been set." Click on OK and the following menu will appear:

First, type the number of the first page of your document in the Enter Page Number field. (In this example the book begins on page 108.)

Next, look at your paper text to see if there are Western numerals printed on each folio side. If there are, then choose the first option, Number on each side of page. If only the Tibetan number of the page is written in the margin of the front side, then choose the Front Side option.

To number every line of every page, check the Insert Line Numbers option.

Click Enter. The page number has now been set and you can insert the page and line number. Again, there are two ways to do this. To insert the first page and line number:

- Click on the "P" button on the THL toolbar, or

- Press Ctrl+1

For line numbers other than the first, use the lineator macro by pressing Ctrl+2 for the second line, Ctrl+3 for the third line, Ctrl+4 for the fourth line and so forth. Be sure that the cursor is placed immediately following the tsheg of the final syllable of the preceding line before inserting the line number. That is, insert the line number before entering the text of that line.

Another way to insert line numbers is to use the THL toolbar, clicking on "2" for the second line number, "3" for the third line and so forth. Again, be sure to insert the line number immediately after the last tsheg of the previous line.

Note: See "Appendix A: Considerations about page numbers" for more things to be aware when dealing with page numbers in a Tibetan text.

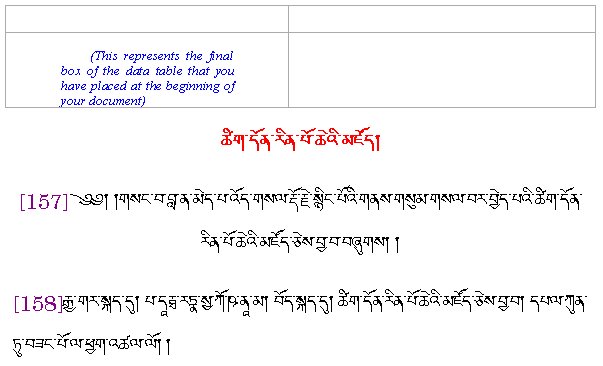

5. Type the Title Page

If your text has a title page, type it immediately following the page number you have just typed. Include the ཡིག་མགོ་ and any spaces in between at the beginning, and the ༎ and whatever else appears at the end of the title. Be sure to include spaces between sets of ༎ if they occur. For example, if you were typing in Longchenpa’s ཚིག་དོན་རིན་པོ་ཆེའི་མཛོད།, and the title page was page 157, it would look like this:

[157]༄༅། །གསང་བ་བླ་ན་མེད་པ་འོད་གསལ་རྡོ་རྗེ་སྙིང་པོའི་གནས་གསུམ་གསལ་བར་བྱེད་པའི་ཚིག་དོན་རིན་པོ་ཆེའི་མཛོད་ཅེས་བྱ་བ་བཞུགས། །

6. Type the First Page of Text

Enter the next page number by pressing Ctrl+1.

Then, begin typing the first page. For the front side of the first page of text, enter this exactly as it appears on the page, including the ཡིག་མགོ. If it is ༄༅༅། then enter that. Note that for all subsequent pages, you should NOT enter the ༄༅། at the beginning of the first line because this is ornamental and is not part of the text.

At this point your text should look like the following:

The centered text is the name of your book in Heading1,h1 style.

The title page (which begins on page 157) comes next. Following this is a hard return, and then the first line of the book (which begins on page 158).

7. Continue Typing and Numbering the Remainder of the Text

At this point, you can proceed to type the remainder of the text. Make sure that your typing stays in the Paragraph,pr style, and that you enter a page number before typing each page.

When you reach the end of a page, press Ctrl+1 (or click "P" on the THL toolbar) to enter the page number for the next page. Make sure the page number is inserted immediately following the final tsheg of one page, and before the first letter of the following page. Remember that no space should be entered either before or after the page number, so the result will look something like this: ཞེས་[231]པ་དང༌།.

Should you make a mistake in entering the page number and need to reset it, you can show the form again without inserting any page or line numbers by pressing Ctrl+0 or clicking the "F" on the THL toolbar. Whenever the form is opened, it will always show the next page number to be inserted. Enter the correct page number and click OK. Then delete the mistake, and insert the page number as you normally would.

8. Text That Should Not Be Typed

Although your goal is to make an exact copy of the paper version of your text, there are a few things that should not be typed into the electronic edition.

- Do not enter the ༄༅། at the beginning of each page, because this is ornamental and is not part of the text aside from its specific formatting for that edition. It is correct to enter the ཡིག་མགོ་ that appears on the first page of the text, but the ཡིག་མགོ་ on the following pages should not be entered.

- Do not type the series of tsheg that is used to fill out a line. For instance, if the end of one line of your text reads བསྟན་པ་དང༌༌༌༌༌༌༌༌, you should just type བསྟན་པ་དང༌

- Do not type the མཆན་རྟགས་, the series of tsheg used to mark a note or མཆན་འགྲེལ་. If the text has མཆན་འགྲེལ་, refer to the section below “Special Situations when Entering Text.”

9. Starting a New File

When your Microsoft Word file is 50 pages long, finish entering the page you are on and then begin a new file.

When starting a new file, simply create a new document as described above. Make sure that you fill out the metadata table for your new file.

Just below the metadata table, enter the page number for the next page that you will type, and continue typing. You do not need to type the title of the text, or anything else. All the metadata needed to identify your new document is in the data table. Just insert the page number and begin typing.

10. Saving and Creating Backups

Computer problems are inevitable, so it is important to save your work often, and create backup copies. It is best to make backup copies of your work on a disk outside of the computer that you are working on. If you have an external hard drive, a flash drive, or some other kind of media, back up your files on this at the end of every work day.

11. Submitting Tibetan Texts

When a text has been fully entered, all the parts of the text along with any scanned images of illegible or unclear parts should be zipped together into a single .zip file, and send to: <a class="safe-contact" href="javascript:linkTo_UnCryptMailto('nbjmup;uimAdpmmbc/jud/wjshjojb/fev');"><img src="/global/images/contact/contact-thl.gif" /></a>, with the subject of the email "Tibetan Text Submission - NAME OF TEXT".

Reference: Special Situations When Entering Text

This section explains some common situations that you will encounter when entering a text: What to do if you find errors, what to do if your text is illegible, what to do if you need to type an unusual character, and so forth.

1. Errors

Your goal is to make an exact reproduction of the paper copy of your text. Thus, if your text contains an error, you should reproduce it when you type. Later, editors will correct the errors in the electronic edition, but they will still want to save a copy of the original file, as it is an exact copy of the paper text.

2. Making Editorial Corrections to Text

In general, THL requires that text input and proofreading be done in a way that preserves the original text. Toward that purpose, text input and proofing should not attempt: 1) to correct mistakes (spelling, grammar, etc.) in the original text; 2) to expand abbreviations or place subscripted/annotated letters into the main line of text; 3) improve the format of the text by adding extra spaces, ornamentation, etc.

If you have the authority to correct errors, then use the following function to provide the original erroneous reading as well as your correction. The idea is to preserve the content of the original document, while also making a note of the editorial correction in a way that conforms to TEI standards.

Immediately preceding the text to be corrected, and before typing it in, press Ctrl+F5 or click the "C" on the THL menu. A form will appear. In the top field, Actual Reading in Text, type the original text as it appears. In the second field, Corrected Reading, type the corrected text. In the third field, Editor's Initials, enter your initials. Click Enter. Continue typing the text.

Using this function will place the original and corrected versions, as well as the initials of the person responsible for the correction in the following format:

<sic corr="Corrected reading" resp="Editor's initials">Actual Reading in Text</sic>

The result will look something like this:

དུས་གསུམ་<sic corr="སངས་རྒྱས་" resp="bjd">སང་གྱས་</sic>གུ་རུ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ།

Do not enter spaces before or after the tags (< >).

3. Collating Different Editions

If you are inputting while checking more than one edition of the text, or actively collating two or more editions of the same text, you should follow all guidelines in this manual, but additionally follow the conventions for citing alternative readings found in the “Variant Readings/Critical Editions” section below.

4. Illegible Text

For places where the text is illegible, type Ctrl+F2 or click the sad face icon on the THL toolbar, which looks like this:

(This will enter in the phrase {Illegible} in a special style), and then begin typing at the next legible syllable. Although the English word “Illegible” now appears in your document, when the document is used to print a book, this can be automatically removed and formatted in an appropriate way.

When documenting illegible text, the page and line number of the text should be noted within the braces to indicate the position of the illegible section. For example, "{ILLEGIBLE[12-3]}" means that illegible text is on line 3 of page (or folio side) 12. Next, a scanned image should be made of just the illegible portion of the line and this image should be named using the edition sigla, dash, the letters "ILL", dash, the pagination as above. Thus, the illustration for the above example would be called "Ab-ILL-12-3.jpg", if the text's sigla was "Ab". Should more than one illegible section occur in the same line, they would be differentiated by using lower case letters, "a", "b", "c", .... Thus, the illegible sections would be marked: "{ILLEGIBLE[12-3a]}", "{ILLEGIBLE[12-3b]}", and so forth, while their corresponding images would be: "Ab-ILL-12-3a.jpg", "Ab-ILL-12-3b.jpg", etc.

The style is named Illegible with the shortcut “il” for those using styles directly.

5. Unclear Text

For places where the text is unclear, make your best guess. Highlight the syllable(s) that are unclear and press Ctrl+F3 or click the footprints icon on the THL toolbar. This marks them in a special style so the reader will know that the original text is unclear. Ctrl+F3 and the footprints icon also toggle on and off the unclear style. To use the unclear function this way:

- Type the ordinary text up until the syllable and tsheg immediately preceding the unclear text.

- Then press Ctrl+F3 or click the footprints icon.

- Type in the unclear text.

- Finally, press Ctrl+F3 or click the footprints icon again to revert back to normal style.

The style is named Unclear with the shortcut “uc” for those using styles directly; it displays in a red font.

6. Typing Special Symbols

The Tibetan Machine Uni font includes a wide variety of Tibetan symbols and punctuation marks. If you are having trouble typing a particular character, one easy way to enter it is with the “insert symbol” command. To enter a symbol in this way,

- Go to Insert.

- Then click Symbol.

- In the Font box, change the font to Tibetan Machine Uni. This will bring up a chart of all the symbols available in the font.

- Highlight the one that you want by clicking on it, and then click Insert.

Following is a list of some special symbols you may encounter which people are often confused by. It is by no means exhaustive and we will amplify only as we see patterns of errors.

a. Visarga ཿ

This is used for the Sanskrit sound that resembles a whispered “h” (in roman transliteration, ḥ). Be sure to input a visarga ཿ and not a gter shad ༔ . The larger circle before the two smaller circles is not part of the visarga character of course – it just stands for whatever letter precedes the visarga.

b. Avagraha ྅

This is a mark used in Sanskrit words to mark that a letter has been elided, such as a short a elided at the beginning of a word. Be sure to use the ྅ and not a ཉ.

c. Che mgo ༸

This is used in Tibetan to mark the name of a holy person and is applied before the name’s first syllable (literally “great one head[-marker]”). Be sure to use the ཆེ་མགོ་ ༸ and not the number 7 ༧. (Notice that the ཆེ་མགོ་ ༸ sits higher than the 7 ༧, though the shape is identical.)

d. Circles Underneath Root Text in Commentaries

Often in commentaries, little circles are placed under syllables cited from the root text. These are also used in other texts for other functions. These are termed འོག་སྐོར་.

The keystroke for the circles under root text in ETWS is an “X” (Shift+x) after the word under which it will appear.

7. Different Types of Shad

All the different types of shad that you encounter should be reproduced exactly as they are in the text.

a. Rin chen spungs shad ༑

A rin chen spung shad is a type of shad which follows a tsheg bar that starts a new line (literally “precious-pile-shad”). These should be entered.

b. Gter shad ༔

A gter shad is a special type of shad used in gter ma texts, and which otherwise functions just like an ordinary shad.

Be sure to input a gter shad ༔ and not a visarga ཿ.

c. Other Types of Shad

The Tibetan Machine Uni font includes a variety of different types of shad: ༎ ༏ ༐ ༑ ༈, and so forth. When you encounter different types of shad in your text, you should reproduce these in your computer file.

If you are having trouble typing the different kinds of shad, refer to the instructions for inserting special characters (topic #4, above).

8. Words in Sanskrit and Other Languages

The Tibetan Machine Uni font is able to reproduce basic Tibetanized Sanskrit characters, but it cannot reproduce unusual characters, complicated mantras, and so forth. If you come across letters that cannot be input, the pages that these are on will need to be scanned and provided with the finished input text. Contact the editor of your project if you come across this problem and he will contact THL (<a class="safe-contact" href="javascript:linkTo_UnCryptMailto('nbjmup;uimAdpmmbc/jud/wjshjojb/fev');"><img src="/global/images/contact/contact-thl.gif" /></a>) to get advice on what to do, which may involve an update of the Tibetan Machine Uni font.

9. Contractions/Abbreviations

Tibetan texts, and especially those using cursive scripts, often use contractions/abbreviations. Such contractions will eliminate a number of characters, and can at times be very difficult to interpret. If your text is written in dbu can script, do not expand contractions or abbreviations. If the text reads ལཌ་ then that is what you must input; do not input ལགས་ instead. Other examples:

- ཉམསུ་ should not be input as ཉམས་སུ།

- ཁྶཾ་ should not be input as ཁམས།

If your text is written in another script, and makes extensive use of བསྐུངས་ཡིག་, then you will need to enter the text using the full spellings of the words, because the བསྐུངས་ཡིག་ will not be able to be reproduced in dbu can script. Consult with the editor in charge of your project if you have a text like this.

10. Mchan ’grel

mchan ’grel refers to the custom of someone writing small notes in a text written by someone else, and then writing a small chain of dots (mchan btags) to connect any given note to the point in the original text to which it applies. If the book that you are typing has མཆན་འགྲེལ་, you should enter it using the following method. The result will not look like མཆན་འགྲེལ་ does in the printed copy of your book. However, when the computer file is used to create a pecha, the མཆན་འགྲེལ་ that you have entered can be automatically formatted to appear in the traditional way.

To type མཆན་འགྲེལ་, you will not enter in the small dots (མཆན་རྟགས་) that lead from the place of insertion to the note. Instead,

(added 4/4/07, by JV: needs to be confirmed and then translated for other versions, and worked into the THL toolbar)

- Insert a footnote in the place where the མཆན་འགྲེལ་ begins.

- In the footnote, put the contents of the མཆན་འགྲེལ་.

- Select the contents of the མཆན་འགྲེལ་ and apply the "Annotation Block,anb" style. Since this is a paragraph style, you can mark individual characters within the མཆན་འགྲེལ་ as "unclear,uc" or with whatever character styles, if any, are appropriate.

The result will have a footnote number in the text, and something like this in the footnote itself: མཆན་འགྲེལ་ཟེར་ཡ་འདི་མཆན་བུའི་ཡི་གེ་རེད།

An alternative method is to first enter in the text of the note at the appropriate location as described above. Then, highlight it and press Ctrl+F1. This will turn the highlighted text into the note style.

Note: The words ཡང་བྱུང་ in the context of a མཆན་འགྲེལ་ are the rough Tibetan equivalent of "variant reading."

11. Parenthesis

For phrases or numbers in some kind of parenthetical marker, press Ctrl+F4 or click on the parenthesis icon on the THL toolbar. This will cause two parenthesis to appear: ༼ ༽. Enter the text inside the parenthesis, and then resume typing on the outside of the parenthesis.

An alternative method is to first enter in the text that has parenthesis around it. Then, highlight this text and press Ctrl+F4 or click on the parenthesis icon. This will place parenthesis around the highlighted text.

Examples of these are in the Fifth Dalai Lama’s gSan yig, there are lineage names(?) parenthetically inserted in the text.

12. Text or Sub-text Embedded within another Text

On occasion you may encounter instances where a sub-text has been inserted into a main text, either by a later author or by a scribe in an attempt to avoid having to re-write the same content repeatedly. In the latter instance, this text is in reality not a separate text from the original but may be written on a separate group of pages which are then referred to in the main text by a few words from the sub-text followed by a “la sogs pa”-the implication being that the scribe wants you to refer to the inserted group of pages for the full content represented by the phrase “la sogs pa.” This is pattern is particularly common in ritual texts where the ritualist must repeat the same words at various times in the course of a long recitation.

In other instances, a later author has inserted pages which supplement the content of the original text. For example, in the khro zur gter chos, a treasure text who's history spans several centuries and authors, later treasure revealers and editors inserted supplementary pages into treasure texts written earlier, sometimes further elaborating or clarifying content written earlier or making more explicit, for example, how to perform a specific ritual.

Whatever the situation, text that is separated from the main text needs to be noted with a footnote which explains what the inserted text is and why it is there.

Note: If the footnote is written in English, make sure to highlight the text using the “English Lang” style in Word. Later, we need to account for these instances- specifically when text is added by a later author- in xml with special attributes.

Below is from Than discussing the various ways to handle this:

“there is some markup to handle these situations, though there may not be rows in the metadata table or macros to deal with the word mark up side. Presuming, the insertions can be considered to belong to the main text, the second author can be considered a reviser or we could even label him/her as second author, though that could be confused with a collaboration between two people. But we can add "responsibility statements" <respdecl>s to account for the role of the second author. (Though, as I said, this may need to be done by hand.) As for additions, there is an <add> element for such a thing that can be attributed to the 2nd author in the metadata, but again I don't think we have a macro for such markup, especially since it spans at least a whole page. This would probably have to be done by hand.

I think a note explaining clearly the situation is probably the best we can do at this point. Also, if there is a comments field in the metadata table about problems etc. It should be noted there. So, that post conversion, the editor can adjust it by hand.”

Variant Readings/ Critical Editions

For an essay on the relationship between various editions of a text and conclusions that can be drawn about the original text, see Peter Robinson’s article  “The History, Discoveries, and Aims of the Canterbury Tales Project” (The Chaucer Review 38.2 (2003), 126-139). Note: this is available online only by subscription, such as through an academic institution.

For marking up a Tibetan text of which there is more than one version, we use footnotes in the Word document to record variant readings. When the XML conversion program is run on the document, these will be converted into apparatus (<app>) tags, and the information provided about the variants, the editions from which they come and their pagination, will all be converted into the appropriate attributes of the <app> tag.

“The History, Discoveries, and Aims of the Canterbury Tales Project” (The Chaucer Review 38.2 (2003), 126-139). Note: this is available online only by subscription, such as through an academic institution.

For marking up a Tibetan text of which there is more than one version, we use footnotes in the Word document to record variant readings. When the XML conversion program is run on the document, these will be converted into apparatus (<app>) tags, and the information provided about the variants, the editions from which they come and their pagination, will all be converted into the appropriate attributes of the <app> tag.

In this document we will use as an example Rongzom’s Bca’ yig (aka Dam bca’), for which we have at present three versions: a manuscript edition, an edition published in India under the PL-480 program, and an edition published in the PRC.

The Siglum

An edition is identified by its siglum (commonly known by its plural, sigla), which is the abbreviation by which the edition is represented. In assigning the siglum you should first check to see if a siglum has already been designated for the publishing house in question (for instance, the siglum “Dg” has been assigned to the Degé Publishing House edition of the Nyingma Gyübum, so other texts from the Degé Publishing House should also have the siglum “Dg”). In the case of Rongzom’s Bca’ yig we are using the sigla “PL” for the PL-480 edition, “PRC” for the PRC edition, and “MS” for the manuscript. Check the  Authority File of Sigla to see if the publisher already has a siglum. If it does not, then assign a siglum and add it to the authority file.

Authority File of Sigla to see if the publisher already has a siglum. If it does not, then assign a siglum and add it to the authority file.

Note: the siglum can be changed after the text is marked up and converted to XML by searching and replacing text in the appropriate attribute of the <app> tag as long as you are consistent in your use of sigla (that is, as long as you use only one siglum for each edition).

Marking up Variant Readings

You will have one edition of the text that you have selected as your base edition, and you will have marked up this edition of the text as a Word document to which you are applying styles for conversion to XML. In the Rongzom example, this is the manuscript edition, which has been input in Wylie.

The format for recording the information about a variant reading is to give the sigla first, followed by the pagination (in the form page.line) in parentheses, followed by a colon, followed by the variant reading.

(changed 4/4/07, by JV: needs to be confirmed and then translated for other versions, and worked into the THL toolbar)

Variant Readings

Add curly braces { } around the syllable(s) in the base edition of the text and insert the footnote after the close curly brace. Do this whether the variant is one or more syllables. If the variant is something like “lha'i” for “lha yi”, please put brackets around [lha yi], not just [yi].”.

Example: the base edition reads བསྙན་དེ་ (bsnyan de) and the PRC reads བརྙན་འདི་ (brnyan 'di) on page 45, line 2. The body of the text looks like this:

- {བསྙན་དེ་}1

- {bsnyan de }1

and the footnote looks like this:

- PL (152.4): བརྙན་འདི་

- PL (152.4): brnyan 'di

Variant Readings in Multiple Editions

If two or more editions have a variant reading for the same syllable and they are different readings, these are separated by a semi-colon. Example: the base edition reads བསྙན་ while the PL edition reads བརྙན་ on page 152 line 4, and the PRC edition reads བརྙེན་ on page 321 line 5, then the footnote looks like this:

- PL (152.4): བརྙན་; PRC (321.5): བརྙེན་

- PL (152.4): brnyan; PRC (321.5): brnyen

If two or more editions have the same variant reading, then the footnote looks like this:

- PL (152.4), PRC (321.5): བརྙན་

- PL (152.4), PRC (321.5): brnyan

Note: When you have a variant reading from more than one edition, you must be consistent in the order the editions appear in the footnote. For instance, we decided that PL will always come first and PRC second.

Variant Readings: Omissions

If a variant reading omits text that is in the base edition, insert curly braces around the syllable(s) (whether one or more) in the base edition, insert a footnote after the close curly brace, and in the footnote enter the sigla of the edition followed by the pagination in parentheses, a colon, and the text “omits”. Example: the manuscript edition reads དེ་ལྟར་ཡོངས་སུ་སྒྲུབ་ན་ (de ltar yongs su sgrub na) and the PL-480 edition reads དེ་ལྟར་སྒྲུབ་ན་ (de ltar sgrub na) on page 405, line 3.

Body of the text:

- དེ་ལྟར་{ཡོངས་སུ་}1སྒྲུབ་ན་

- de ltar {yongs su }1sgrub na

Footnote:

- PL (405.3): omits

Variant Readings: Insertions

Another case is if a variant reading adds text that is not in the base edition. For example, the manuscript reads ལས་ཀྱིས་ (las kyis) and the PRC edition (204.6) reads ལས་ཐམས་ཅད་ཀྱིས་ (las thams cad kyis). In this case, do not put any brackets in the main part of the texts, but rather add a footnote at the point of insertion. The footnote goes exactly where the omission would be, so it follows a space and is at the beginning of a syllable. For example -

Body of the text:

- ལས་1ཀྱིས་

- las 1kyis

Footnote:

- PRC (204.6): ཐམས་ཅད་

- PRC (204.6): thams cad

Guidelines for placing footnotes

It is important that footnotes are placed in the correct place in relationship to tsheg and shad, whether you are marking up a Tibetan script or Roman script edition.

In general, footnotes most be placed after the tsheg following a word, and NOT before it. If the critical edition is in Wylie, this will look strange since it means the footnote will be placed after the space following a syllable, and immediately adjacent to the following syllable without intervening space. Thus:

- ལས་1ཀྱིས་

- las 1kyis

If a footnote is attached to a syllable at the end of a line, then generally a shad will follow the syllable rather than a tsheg. In this case, the footnote should be placed after the shad. If there is a double shad at the end of the line, such as in verse, place the footnote directly after the first shad and before the white space + second shad. An exception to this would be if one is documenting a missing shad. For example, say the baseline text has two shad, and one is documenting a variant that only has one shad, then the footnote should be placed after the second shad. However, if the final letter of the line is a “ng”, then there is a tsheg prior to the shad. In that case, place the footnote after the tsheg but before the shad. If the final letter of the line is a “g”, then there is a white space before the shad. In that case, place the footnote directly after the “g” and before the white space. Examples:

- དོར།1 །

- དང་2 ། །

- དག3 །

Guidelines for combining footnotes

In general, we want to consolidate foonotes when possible. For example, if you have annotations that are placed in different locations in different editions, but there is no significance to the slight variation, you should choose the best location and insert a combined footnote therein seperating the two readings by a semi-colon (see below "Multiple texts have the same mchan 'grel in different places"). The same goes for if you have more than one variant to note. The general practice should be to separate the various things with semi-colons + space, and then have a final period. However, NEVER combine in one footnote annotations and variant readings - these should always be given in separate footnotes. The reason is that this allows us to visually present annotations and variants in different ways according to user specification. That will allow users to focus on just looking at variants, or just looking at annotations, without being required to look at them together.

Preferred Readings

If you want to indicate a preferred reading, use an asterisk (*) before the sigla. For example, to indicate that in the above example the PL-480 reading is the preferred reading:

* PL (152.4): brnyan; PRC (321.5): brnyen

Mchan ’grel

(added 4/4/07, by JV: needs to be confirmed and then translated for other versions, and worked into the THL toolbar)

The method for inputting མཆན་འགྲེལ་ from multiple readings is the same as the mchan 'grel description above, with the following exceptions:

Put the siglum at the beginning of the footnote, without the page.line reference, followed a colon, followed by the མཆན་འགྲེལ་ contents. For example:

- PL: མཆན་འགྲེལ་ཟེར་ཡ་འདི་མཆན་བུའི་ཡི་གེ་རེད།.

Multiple texts have the same mchan 'grel in the same place

If multiple texts show the same མཆན་འགྲེལ་ in the same place, separate the sources with a comma. For example:

- PL, PRC: མཆན་འགྲེལ་ཟེར་ཡ་འདི་མཆན་བུའི་ཡི་གེ་རེད།.

Multiple texts have the same mchan 'grel in different places

If multiple texts show the same མཆན་འགྲེལ་ in different places, make a judgment about which location is more accurate, footnote it there, and enter the མཆན་འགྲེལ་ variants together in the footnote, separated by a semi-colon. After any མཆན་འགྲེལ་ that you have moved from their original locations, insert a space and then a parenthetical statement describing the original location. For example:

- PL: མཆན་འགྲེལ་ཟེར་ཡག (formerly in this segment between གཉིས་ and ལ་); * PRC: མཆན་འགྲེལ་ཟེར་ཡ་འདི་མཆན་བུའི་ཡི་གེ་རེད།.

Multiple texts have different mchan 'grel in the same place

If multiple texts show different མཆན་འགྲེལ་ in the same place, they are marked in a manner similar to variant readings. For example:

- PL: མཆན་འགྲེལ་ཟེར་ཡག; * PRC: མཆན་འགྲེལ་ཟེར་ཡ་འདི་མཆན་བུའི་ཡི་གེ་རེད།.

Note that, in this case, we decided that both texts were going for the same མཆན་འགྲེལ་, instead of making different comments. As a result, we marked the preferred reading with an asterisk (*). Had they been dramatically different comments, but both logical, it would not have been appropriate to make a preferred reading.

Proofing and Quality Control

In addition to being consistent in the practices used to input a text, the most essential thing is not making errors. Electronic texts are of very limited value if errors are introduced in the input process. People who use them will perpetuate the errors, while searches done will give deceptive results. Thus work must be done carefully from the beginning, and careful proofing of the input against the original manuscript is key.

One important way to minimize error in input is to do “double input”. This involves two different people inputting the same text, and then using Word to compare the input and highlight the differences. An editor then needs to proof the result. However it is true this is more expensive and time consuming since it involves two different inputs.

Regardless of whether one has single input or double input, the following are some basic guidelines for ensuring good quality proofing.

- At least one proofer must be different from the person who inputs the text – otherwise someone proofing their own input text at some point will just not be able to see their persistent errors.

- Proofing must take place by reviewing a print out of the input text, not simply reviewing the input text by looking at the computer screen. No one can proof well from a computer screen.

- Proofing must take place against the original text, not simply by looking at the input text – otherwise there is no possibility that proofing can verify correspond to the original text, errors and all

- In proofing, turn on view of tabs, spaces and paragraph marks to see particular problems there (in Word, Tools>Options>General>Formatting Marks).

- In Tibet, a standard practice is to have one person read the input text out loud and a second person listen and read the original manuscript. We do not think this is a useful procedure to do good proofing. Homonyms are impossible to catch, the speed is often to fast to do careful work, and in general many errors remain which anyone doing a visual inspection of the input text and original manuscript would catch.

A related practice is to have one person reading the input text actually spelling out each word, including spaces and punctuation. Thus it would like “s-t-a-r-t-space-t-h-i-s” etc. But for lengthy texts one has to wonder if this is really practical, and again whether people don’t speed up to save time, and hence again fail to catch serious errors.

Metadata Table

This is the table that should be at the beginning of every file. If there are multiple files representing a single text, each should have this table at the beginning. “Metadata” simply means information about the text (metadata) rather than the text itself (data). The table here includes descriptions of each field in the right hand column but these should be replaced by the actual information.

Note: This table does not appear exactly the way it appears in the Word doc, so please refer to the Word doc if there are any questions.

| Metadata Table | |

|---|---|

| དེབ་བམ་དཔེ་ཆའི་མིང་། | |

| Title of Text | This is the full title of the text in Unicode Tibetan |

| དེབ་བམ་དཔེ་ཆའི་ཁ་བྱང་། | |

| Cover Page | This is the full text of the cover page in Unicode Tibetan. The cover page is the first printed page in non dpe cha books. |

| དེབ་བམ་དཔེ་ཆའི་ཁ་ཤོག་གི་མིང་། | |

| Title on Cover | This is the full title of the text on the cover page in Unicode Tibetan |

| དེབ་བམ་དཔེ་ཆའི་ཟུར་གྱི་མིང་། | |

| Title on Spine | This is the full title of the text on the spine of the book in Unicode Tibetan |

| དཔེ་ཆའི་ཁ་བྱང་། | |

| Margin Title | This is the full title of the text in the margin in Unicode Tibetan. This usually appears on the front-side of each folio for dpe cha style books or books that contain photographic reproductions of dpe cha style books |

| རྩོམ་པ་པོ། | |

| Author of Text | This is the full name of the author in Unicode Tibetan |

| ཕྱོགས་བསྡུས་ཀྱི་མིང་། | |

| Name of Collection (if applicable) | If the work is included in a multi-volume collection, enter its name here in Unicode Tibetan. |

| དཔེ་སྐྲུན་ཁང་གི་མིང་། | |

| Publisher Name | This is the name of the publisher as it appears in the publication statement either in the front or back of the text in the language it appears. |

| དཔེ་སྐྲུན་ཁང་གི་གནས་ཡུལ། | |

| Publisher Place | This is the place of publication as it appears in the publication statement. |

| དཔེ་་སྐྲུན་དུས་ཚོད། | |

| Publisher Date | This is the date of publication as it appears in the publication statement. |

| ISBNཨང་རྟགས | |

| ISBN (if applicable) | If the publication statement includes an ISBN number, place it here. |

| མ་ཕྱི་དཔེ་མཛོད་ཁང་གི་CIP་ཨང་རྟགས། | |

| Library Call-number (if applicable) | If there is a University library call-number, include it here. |

| ཨང་རྟགས་གཞན། | |

| Other ID number (if applicable) | Any other ID information about the text should be included here. |

| པོ་ཏིའི་ཨང་རྟགས། | |

| Volume Number (if applicable) | If the text is in a multi volumed collection, the volume number within that collection. |

| དེབ་བམ་དཔེ་ཆའི་ཤོག་གྲངས་དང་ཡིག་ཕྲེང། | |

| Pagination of Text | The pagination of the text in the volume including line numbers. This would be either in the format, 58.4-103.7 or 24b.3-78a.6 depending on whether page numbers were printed on both sides or just one side of the folio. |

| གློག་ལས་ནང་གི་དོན་ཚན་གྱི་ཤོག་གྲངས། | |

| Pages Represented in this file | The pages included in the present file. If there is just one file for a text, this will be identical to above. If there are several files for a text, this would represent the pages transcribed in the present file. |

| ཕབ་བསྒྱུར་མཁན་གྱི་མཚན་། | |

| Name of Inputter | The full name of the inputter. If more than one person was involved in inputting, multiple names can be included here, followed by the pages they input and separated by carriage returns (enter-s). |

| ཕབ་བསྒྱུར་འགོ་ཚུགས་ཀྱི་དུས་ཚོད། | |

| Date Inputting Begun | Date that the input for this text began in the format: YYYY-MM-DD. |

| ཕབ་བསྒྱུར་མཇུག་སྒྲིལ་གྱི་དུས་ཚོད། | |

| Date Inputting Finished | Date that the input for this text was finished in the format: YYYY-MM-DD. |

| ཕབ་བསྒྱུར་གྱི་གནས། | |

| Place of Inputting | Place where inputting occurred in the format: City, State/Province, Country |

| ཕབ་བསྒྱུར་གྱི་ཐབས་ཤེས། | |

| Method of Input | This is the method used to input the text including names of keyboards, fonts used, program used, etc. |

| ཞུས་དག་མཁན་གྱི་མཚན། | |

| Name of Proofreader | This is the full name of the person who proofread the input version of the text against the original text. If more than one person was involved in the proofing, multiple names can be included here, followed by the pages they proofed and separated by carriage returns (enter-s) |

| ཞུས་དག་འགོ་ཚུགས་ཀྱི་དུས་ཚོད། | |

| Date Proofreading Began | Date that proofreading for this text began in the format: YYYY-MM-DD |

| ཞུས་དག་མཇུག་སྒྲིལ་གྱི་དུས་ཚོད། | |

| Date Proofreading Finished | Date that proofreading for this text was finished in the format: YYYY-MM-DD |

| ཞུས་དག་བཏང་སའི་གནས། | |

| Place of Proofreading | Place where proofing occurred in the format: City, State/Province, Country |

| རྟགས་བརྒྱབ་མཁན་གྱི་མཚན། | |

| Name of Markup-er | This is the full name of the person who marked-up the text in MS Word styles. If more than one person was involved in the markup, multiple names can be included here, followed by the type of markup they did and separated by carriage returns (enter-s) |

| རྟགས་བརྒྱབ་འགོ་ཚུགས་ཀྱི་དུས་ཚོད། | |

| Date Markup Began | Date that the markup of this text began in the format: YYYY-MM-DD |

| རྟགས་བརྒྱབ་མཇུག་སྒྲིལ་གྱི་དུས་ཚོད། | |

| Date Markup Finished | This is the date that the markup of this text was finished in the format: YYYY-MM-DD |

| རྟགས་བརྒྱབ་སའི་གནས། | |

| Place of Markup | |

| དོགས་གནད་གསལ་བཤད། | |

| Problems/Anomalies | Any problems or anomalies with the text entry and representation should be noted here with the name of the person noting them following in parentheses. If there are multiple problems, these should be separated out into separate paragraphs within this cell. |

| འགྱུར་ལྡོག་བཏང་མཁན་གྱི་མིང། | |

| Name of Converter | This is the full name of the person who converted the MS Word file of the text into an XML document. If more than one person was involved in the conversion, multiple names can be included here, followed by the role they had and separated by carriage returns (enter-s) |

| འགྱུར་ལྡོག་བཏང་འགོ་ཚུགས་པའི་དུས་ཚོད། | |

| Date Conversion Began | This is the date that the conversion of this text to XML began in the format: YYYY-MM-DD |

| འགྱུར་ལྡོག་བཏང་མཇུག་སྒྲིལ་བའི་དུས་ཚོད། | |

| Date Conversion Finished | This is the date that the conversion of this text to XML was finished in the format: YYYY-MM-DD |

| འགྱུར་ལྡོག་བཏང་སའི་གནས། | |

| Place of Conversion | Place where conversion occurred in the format: City, State/Province, Country |

Appendix A: Considerations about Page Numbers

- Manuscript page/line numbers

Many pecha-style texts are numbered by folio, rather than by page-sides (as in Western-style pagination). When referring to the sides of a folio thus, you may refer colloquially in Tibetan to its "front" (Tib. mdun) and "back" (Tib. rgyab). In response to this, one convention that has been adopted is to designate page numbers by the folio number followed by "a" for the front side and "b" for the back side. Thus, the first folio of a text would have two sides: "1a" and "1b." Some Tibetan texts presently also have adopted the practice of numbering the pages with Western style numbers on each page-side.

Sometimes a text has two pages with the same number, with གོང་ or གོང་མ་ and འོག་ or འོག་མ་་added to differentiate the pages. For example, རེ་དྲུག་གོང and རེ་དྲུག་འོག. The pagination is written in arabic numbers as 66A and 66B, so the front side of རེ་དྲུག་གོང is 66Aa and the back side is 66Ab. The front side of རེ་དྲུག་འོག is 66Ba and the back side is 66Bb. (note: this paragraph was added 2017-07-19, so it needs to be added to the Tibetan and Chinese translations of this manual)

You may choose to accept the numbering already written in the Tibetan text or not. Sometimes page numbers found in a text are either unclear or else have other problems, requiring that new numbers be written. If you must write in new numbers yourself, please be certain to apply your numbering system consistently throughout the entire collection that you are working with. For example, if each volume in a thirty-volume collection of treasure texts has its own table of contents (dkar chags) in Tibetan, if you include the table of contents in the numbering sequence for volume one, you must include the table of contents for volume two in volume two's numbering. In other words, apply the same style of numbering universally for all of the items in a collection. Consistent numbering practices make it easier to process the texts later, especially cataloging. Bodies of texts with idiosyncratic numbering styles may create more work for other staff who prepare the text for final publication later on. (Note: Whatever style numbering you adopt, the Page-Inserter function in THL's Tibetan Input Template handles most of the common numbering permutations).

- Digital page/line numbers

Ultimately, we advocate readers of electronic editions - whether using them online or offline in printed out versions, should use the new digital lines and pages for reference purposes. Every 20 syllables is counted as one line, and every 300 syllables is counted as one page. Thus every digital page has 15 lines. These digital lines/pages are inserted when using a THL program when the edition has become stabilized and is ready to be published. There will no doubt be corrections made post-publication, which will cause the page/line totals to sometimes vary slightly from 20/300, but that is acceptable and preferable to changing the page/line numbers post-publication. We will make changes to the digital page/lines only if a major mistake has been made and an electronic edition has been published with significant mistakes involving missing or extra text.

Appendix B: Inputting with a pre-made catalog

For the Kangyur input project, we re-worked the input process substantially. In the original method outlined in the main part of this document, the inputter first had to fill out a great deal of information in the metadata table every time s/he opened a new file. This not only wasted a great deal of time but led to a number of errors owing to inputters not understanding exactly how to fill out the table or else forgetting to fill out certain parts. Further, some of the information in the original metadata table (such as the "Pages Represented in this file", for example) can be collected automatically with custom-made macros (in Microsoft Word or OpenOffice Writer) after inputting is finished. Thus, the decision was made to simplify the meta-data table as much as possible so as to increase the efficiency of the input process, minimize the chance of error-ridden input, and make work more pleasant for the input staff. The result is that we've separated the collection of textual metadata and the input process entirely. Rather than an inputter filling out a complex table with information about the author, place and time of publication, etc. a separate cataloger does this beforehand. As the cataloger collects this information, s/he assigns a unique ID number to each text s/he catalogs in a volume. When finished, this catalog is provided to inputters. When entering a new text, the inputter need only enter her name, location, date of input, the texts volume letter (ka, kha, etc) and the text's unique ID number. The ID number is crucial; without it there would be no way to connect an e-text file (the Word or OpenOffice document) with the corresponding metadata in the pre-made catalog.

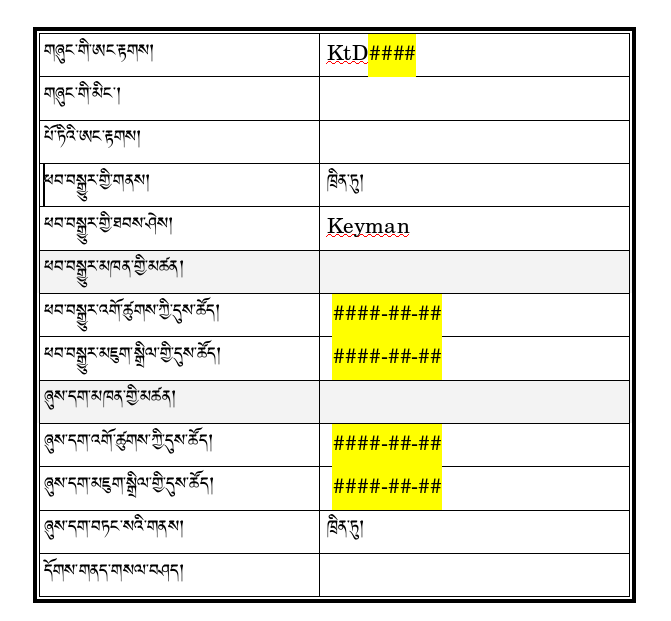

Here is the special metadata table provided in the custom made input template for the Kangyur input project:

Note how the majority of fields from the original table have been removed. Note also the ID field. In this case, the "KtD" part of the ID is a sigla which stands for "Kangyur-Tengyur Dege Edition". The letter sigla needs to be followed by a four digit, text-specific number found in the pre-made Kangyur catalog. Inputters delete the sections in yellow and input actual information related to date and text they are inputting. Bright yellow helps remind the inputters this information must be filled out (note that all of the fields must be filled-out; the fields marked in yellow are either extremely important or otherwise often forgotten). In this case, the inputters are based in Chengdu (written as ཁྲིན་ཏུ་ in Tibetan), PRC. Because no Kangyur input will be done outside of Chengdu, that information has been pre-provided in the table (as has the "Keyman" input method). Finally, notice the absence of English: this was simply extra content that only cluttered the page for our non-English speaking staff.

This method of input using a pre-made catalog could be pursued as an alternative the method outlined in the body of this document-so long as the cataloger makes certain to collect all of the data ommited from the original metadata table. Absolutely required in a pre-made catolog are the following:

- Title

- Author

- Pagination

- Place of Publication

- Publisher

- Date of Publication

Also important is the margin title (if the text is a formatted as a traditional pecha), the name on the cover page, the volume number, and the name of the collection from which the text derives (e.g. "rnying ma rgyud 'bum"), if applicable. See the Text Markup - Metadata wiki for a fuller description of THL's metadata guidelines.

Appendix C: Common Input Errors

Below are some commonly encountered input errors from past input work.

Typos resulting in a correctly spelled, but wrong word

Inputters sometimes fail to notice that they have mistyped a word when the result is not a mispelled word. For example, one common error is to type ཁང as ངག. These types of mistakes are easy to make, especially when typing quickly.

Entering the yig mgo ༄༅ on every new folio or at the beginning of every document

A yig mgo is only necessary at the very beginning of a text. Thus, although you will typically see a yig mgo on the front (or "a" side) of every folio, only the very first yig mgo at the beginning of a text is needed. Note this does NOT mean a yig mgo is needed at the beginning of every document. Sometimes a text spans many Word or OpenOffice files. A yig mgo is only need for the first file of that text.

Extra spaces are added before and after the page/line numbers

For example, the following two liines are incorrect:

- སེམས་ཅན་ [200b.3]ཐམས་ཅད

and

- སེམས་ཅན་[200b.3] ཐམས་ཅད

The first example leaves a space before the page/line number. The second has a space after. Unless the text unambiguously has these spaces (which would be very difficult to determine visually), no spaces should precede of follow a page/line number.

Failure to fill in the "Date Input Finished" field in the metadata table or filling out the date partially or in an incorrect format

It is easy to forget to enter in the date after you finish inputting a text. Many inputters simply close the document when finished and forget to fill out this information entirely, only to realize later that this information is missing. As a result, sometime inputters guess a date or only put something vague such as only the year or a short note. Thus, it is essential to remind yourself or the inputters you are working with not to forget to enter the date!

Unclear file names and storage conventions

Files should include information that helps other people working with these texts infer what is in the file. Thus, file names with sigla information, page, genre, and/or volume information are generally helpful. By contrast, a file named "'dul ba 3.doc" is too vague. Does this mean volume 3 of the 'dul ba section of the Kangyur? Or is it the third document in volume 1 of the 'dul ba section of the Kangyur? Exceptionally long file names should also be avoided (thus, you probably wouldn't name a file after the name of the text you are inputting). Finally, files should be stored in a way so they are easy to find later. Saving files to a separate folder for each volume in a collection is a good idea, though anyt method that is clear and easy for other people to navigate is fine.

Appendix D: Inputting Using a Non-Windows Operating System and Software

Although we have been using Windows and Microsoft Word for all of our text input work to date, you may want use another operating system and word processor like Mac OS X, Linux and OpenOffice.org. Right now THL provides no support for word processors other than Word, therefore anyone using alternative methods should be in contact with THL staff before starting the input process. Below is some very general information for those using Tibetan in an operating system other than Windows.

For Linux, many versions of Debian with Gnome include support for the Dzongkha Tibetan keyboard. Newer distributions should also have a version of the CNS or "Vista" style keyboard. Alternatively, popular input methods like SCIM and UIM in Linux can be configured for inputting Tibetan in Wylie using the m17n library. The functionality of SCIM and UIM is almost identical to that of TISE in Windows. Further, the Bhutanese government has put many years into creating a Dzongkha language linux operating system with full support of Tibetan unicode which may be helpful for use in Bhutan and Tibet. This is available for free at  Sourceforge.

Sourceforge.

OpenOffice.org 2.1 and higher has support for Tibetan Unicode on Linux, Mac, and Windows. MS Office 2008 does NOT presently support Tibetan on Mac OSX.